The Art of Writing Is the Art of Applying the Seat of the Pants Means

Winter 2008–2009

To Sit down, to Stand up, to Write

The author'south position

George Pendle

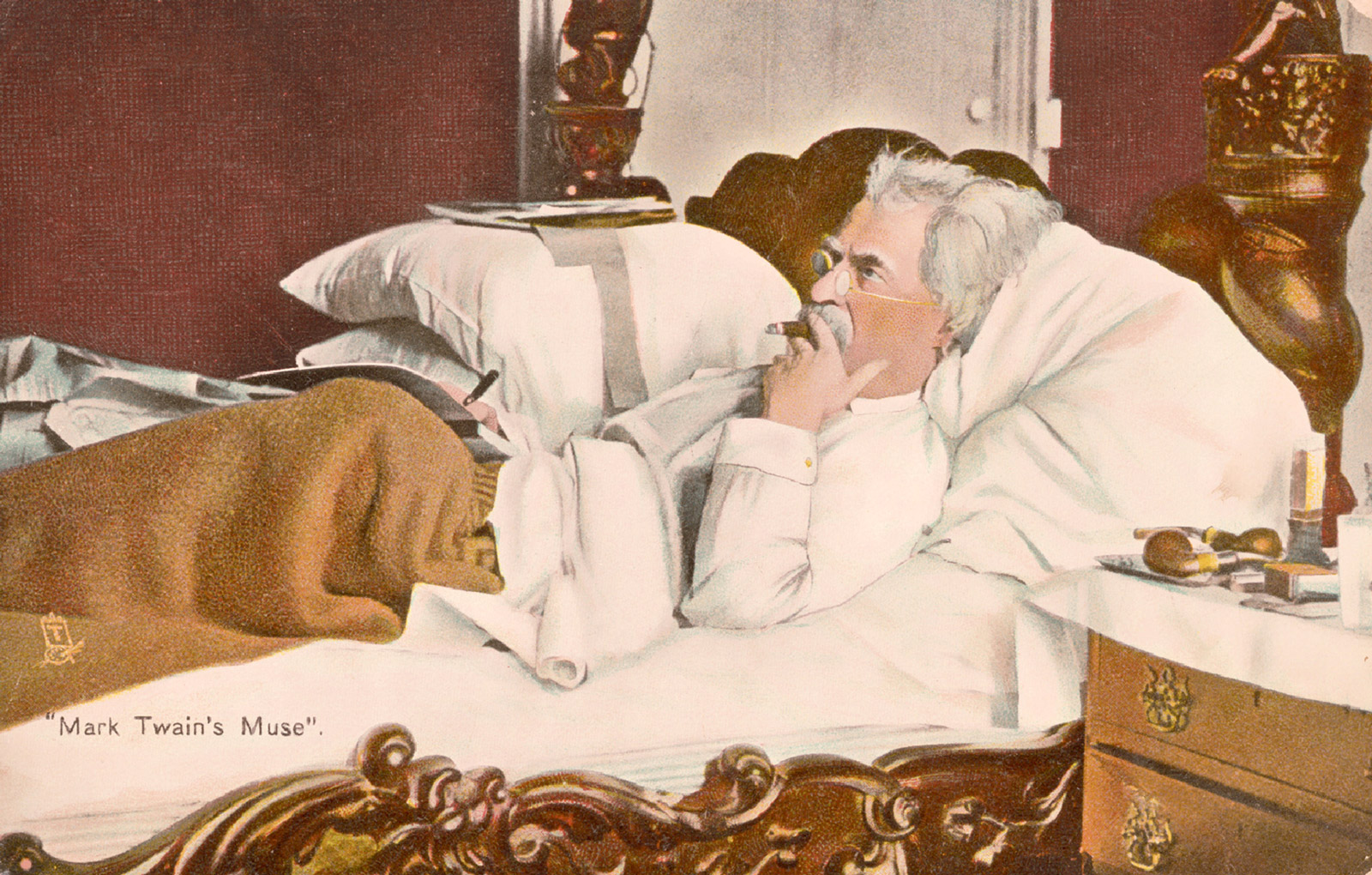

Tuck's Postcard showing Mark Twain at work, ca. 1900. Courtesy Barrett Collection, Special Collections, Academy of Virginia Library.

One of the more curious denouncements to appear in Friedrich Nietzsche'southward supremely truculent Twilight of the Idols (1888) is a brief merely furious attack on the writing habits of Gustave Flaubert. In a alphabetic character to Guy de Maupassant, his protégé, Flaubert had made the seemingly innocuous statement: "One cannot recollect and write except when seated." The author of Madame Bovary (1856) had ever been a sedentary sort and had previously informed Maupassant that "a civilized person needs much less locomotion than the doctors claim." However, to Nietzsche'due south ear, finely attuned to the slightest signs of cultural decadence, Flaubert'south admission was zippo less than an assault on the nature of creativity itself. "In that location I have caught you lot, nihilist!" he snapped triumphantly. "The sedentary life (das sitzfleisch—literally "sitting meat") is the very sin confronting the Holy Spirit. Merely thoughts reached past walking have value."

Ever since Nietzsche's announcement, in that location has been some disagreement amid writers, thinkers, doctors, and designers as to whether inspiration and inventiveness come from existence seated and quiescent, or from being upright and vigorous. (Full disclosure: This article is being written standing up.) It was the early twentieth century labor journalist and suffragette, Mary Heaton Vorse, who pithily described the fine art of writing every bit "the art of applying the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair." Vorse was expressing a distinctly Flaubertian sentiment that was all the more radical when one considers how few women wore pants at the time. Ernest Hemingway, past contrast, proved to exist a strict Nietzschean, declaring that "writing and travel broaden your ass if not your mind and I like to write continuing up," which he did by perching his typewriter on a breast-loftier shelf, while his desk became obscured by books.

Yet trying to find out whether authors who share similar writing positions also share like writing styles is by no means easy. Such disparate authors every bit Virginia Woolf, Lewis Carroll, and Fernando Pessoa all wrote standing up, while Mark Twain, Marcel Proust, and Truman Capote took the Flaubertian creed to its ultimate extent by writing while lying downwards. Indeed, Capote went so far every bit to declare himself "a completely horizontal writer."

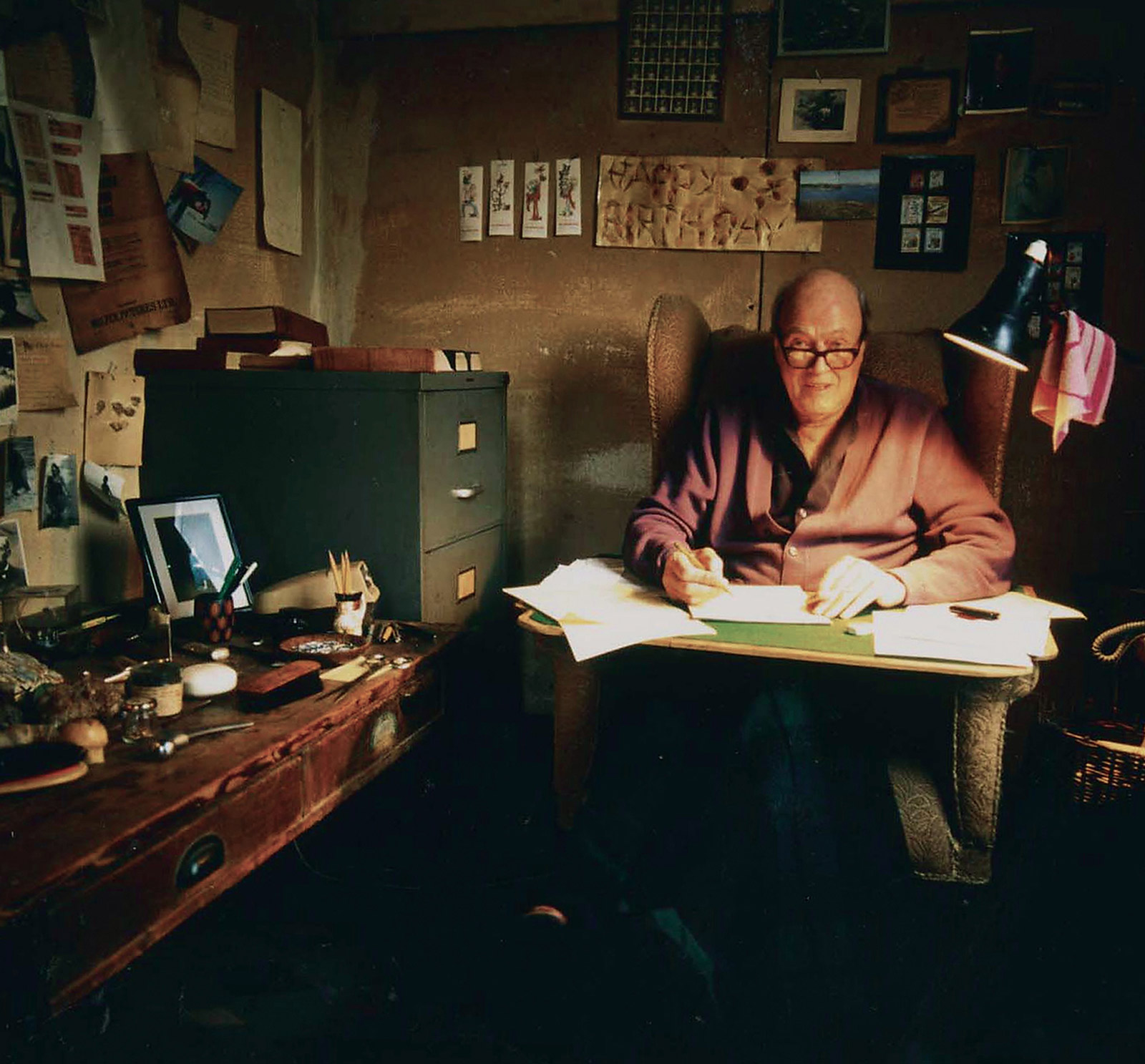

We can conjecture that it was physical considerations that caused the six-human foot-half-dozen-inch Thomas Wolfe to write his opulent, autobiographical novels using the peak of the refrigerator as his desk, the shifting of his weight from foot to foot being a dandy approximation of the Nietzschean decree that all writing should "dance." But what do we and so make of Roald Dahl, also six-human foot-six, who everyday climbed into a sleeping bag earlier settling into an old wing-backed chair, his feet resting immobile on a battered traveling case full of logs? Dahl's merits that "all the best stuff comes at the desk," is a unproblematic mod variation on Flaubert's static dictum.

Roald Dahl in his writing hut, ca. 1990. Copyright Jan Baldwin. Courtesy the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre.

Occasionally the hint of a philosophical similarity can be drawn betwixt those who share the aforementioned manner of writing. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.—the Supreme Court justice who coined the phrase "articulate and nowadays danger" to limit the First Amendment when its do endangered the country—wrote his concise legal opinions while continuing at a lectern because "nothing conduces to brevity like a caving in of the knees." Such a sentiment seemed to be echoed, albeit in a somewhat distorted way, past another fellow member of the federal government (and boyfriend vertical author), the former secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld. When Rumsfeld was handed a list of approved torture techniques being used at Guantanamo Bay, he infamously scribbled a query on information technology: "I stand up for 8–10 hours. Why is standing [of prisoners] limited to 4 hours?"

If we look to prehistory for guidance on the platonic artistic posture, we gain only indistinct clues. In the Book of Genesis, we hear that as God created the heavens and the globe He "moved upon the face of the waters." While this suggests that He wasn't following the Flaubertian prescription of motionless creativity, what He was doing seems more like sailing or canoeing—Noah's ark is also described equally "moving upon the confront of the waters"—neither of which activeness entirely meets the orthodox Nietzschean standard.

History is not much more helpful. Aristotle's followers were known as Peripatetics, although no i is entirely sure whether this stems from Aristotle's habit of walking well-nigh while he talked (his followers taking their name from the word peripatêtikos, meaning "given to walking about") or because he held lessons beneath the colonnades (or peripatoi) of the Lyceum.

Ernest Hemingway prefered to write standing up.

Etymological study initially seems to favor the Nietzschean attitude of being vital, upright, and mobile in the moment of one'south creation. The aboriginal Greek word theoria—from which the word theory stems—included within it the thought of a journeying, in detail a pilgrimage undertaken to the abode of a god or goddess. Nevertheless modern words seem to lean towards a supine Flaubertianism; after all, surely the modern English homophones stationary—meaning motionless—and stationery—meaning writing paper—audio the same for a reason.

In 1967, Jacques Derrida attempted to quash the whole argument in Writing and Difference, insisting that Nietzsche was being disingenuous in his assault on sitting and writing. "Nietzsche was certain that the writer would never be upright," Derrida insisted. Even Zarathustra eventually had to stop "tracing figures of fire in the heavens" and hunch down over a desk-bound since "writing is get-go and always something over which one bends."

The vast majority of the world would concord with Derrida. Since its heyday in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the standing desk has go almost obsolete, and today in offices and libraries in every continent, workers are leap to their desks similar Prometheus to his rock. Simply the gimmicky office environment owes less to the persuasiveness of Flaubert and Derrida than to a designer named Bob Propst.

In 1968, Propst, a former professor of fine arts who had become head of inquiry at the Herman Miller company, surveyed the common office space and alleged information technology a wasteland. Row later on row of orderly desks and chairs stretched to the horizon, and filing cabinets reached up to the sky (see Billy Wilder's 1960 film The Flat). The "monolithic insanity" of it was abomination to creation. "It saps vitality," Propst asserted, "blocks talent, frustrates accomplishment. It is the daily scene of unfulfilled intentions and failed effort." Propst declared that he wanted offices to be less soulless and let workers to circulate more freely. "It'due south truly amazing the number of decisive events and disquisitional dialogues that occur when people are out of their seated, stuffy contexts."

Although he may not take known information technology, Propst seemed to be directly channeling the posture theories of Nietzsche who, in The Gay Scientific discipline (1882), had linked the deleterious issue of a bad workspace (and bad digestion) to the quality of a person'south work: "How rapidly we guess how someone has come by his ideas; whether it was while sitting in front of his inkwell, with a pinched belly, his head bowed depression over the paper—in which case we are quickly finished with his book, too! Cramped intestines betray themselves—you can bet on that—no less than closet air, closet ceilings, closet narrowness."

According to Quentin Bong, Virgina Woolf's nephew and biographer, Woolf "had a desk continuing nigh three anxiety six inches high with a sloping height; it was so high that she had to stand to her work." This work habit connected until nearly 1912. Later in her life, Woolf often wrote in a low armchair with a plywood board beyond her knees.

Propst's respond to the "closet narrowness" of the mid-twentieth-century office was what he chosen the Action Office System. A truly Nietzschean accomplishment, the Action Office System used moveable partitions to create free-wheeling semi-enclosed spaces that offered a social kind of privacy. Varying desk levels immune employees to work continuing up, thus encouraging blood flow, and management would be readily approachable, non subconscious away in an part. It was intended as "a low-key, unself-witting product" that changed the very position in which people worked.

But every bit with so many other Nietzschean ideals, the Action Office Arrangement was seized upon by unscrupulous individuals and twisted out of shape. Companies soon realized that the moveable partitions of the Action Part Organization could exist used to cram more than and more than workers into smaller and smaller spaces. The varying desk levels were removed as being inapplicable, the holistic experience was betrayed, and soon Action Office partitions were lined up in identical rows, every bit desks had been before them (meet Mike Judge's Office Space, from 1999). Nihilism had returned. The Action Function system had become the cubicle.

The stunning corruption of Propst'due south Nietzschean ideals made information technology seem as if the Flaubertian schoolhouse of posture had triumphed for good. Simply in 2005, Dr. James Levine, an endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, created what was possibly the fullest apotheosis of the Nietzschean posture platonic to engagement.

Levine is an expert in North.Due east.A.T., or not-exercise action thermogenesis. Using custom-made information-logging undergarments with motion-sensing engineering science, Levine measured how many calories we burn down through in our simple solar day-to-twenty-four hours activities. His remarkable discovery was that slender people are on their anxiety an boilerplate of 152 more than minutes a 24-hour interval than overweight people. His ingenious solution was to invent a treadmill desk-bound—a computer final with a treadmill taking the place of a chair. Noticing that the sedentary Flaubertian fashion of working barely used any calories at all, Levine showed that merely walking at i mile per hour while writing and making telephone calls could burn approximately 125 calories per hour. Levine now sells such "walkstations" for $4,000 each.

Admittedly Levine's walkstations are primarily aimed at those who wish to lose weight, rather than those who wish to create undying philosophical works of eternal value. Even so, it is the most significant vertical riposte to the stock-still Flaubertian immobile in many years.

George Pendle has written for the Times, the Financial Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. He is the writer of Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons (Harcourt, 2005), The Remarkable Millard Fillmore: The Unbelievable Life of a Forgotten President (Three Rivers Printing, 2007), and the recently published Expiry: A Life (Three Rivers Printing, 2008). He is currently writing an in-depth study of airport carpeting.

If y'all've enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You lot get twelve online issues and unlimited admission to all our archives.

Source: https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/32/pendle.php

0 Response to "The Art of Writing Is the Art of Applying the Seat of the Pants Means"

Post a Comment